Earlier today, I released version 0.2.0 of Gliss, a lightweight tool for inspecting and processing tagged annotations in git repositories. Since I last wrote about gliss, there have been a few improvements worth mentioning; I’ll briefly go over them here:

-

Support for malformed glosses. The gliss conventions specify that a gloss tag must start at the beginning of a new line. If you have some commits that don’t follow the conventions, though, you might miss their glosses. By using the

–permissiveoption, you can find gloss candidates that are indented or that start in the middle of the line. -

Support for multiple tag filters. In previous releases of gliss, you could use the

–filteroption to specify a regular expression that all printed tags must match. Now, supplying multiple–filteroptions will return all glosses that matchanyof the provided expressions. -

Support for printing the whole commit in which matching glosses appear. The

–whole-commitoption (`-w for short) will cause gliss to print every commit containing a matching gloss. You may need this option if you’re compiling release notes and the gloss text for a given gloss doesn’t contain enough context. -

Support for Markdown-formatted glosses. If you have the Maruku gem installed, gliss can treat glosses with certain tags as containing Markdown-formatted text and render them in well-formed HTML or LaTeX. Use the

–format-glosses-matchingoption to specify regular expressions for gloss tags whose texts should be rendered via Markdown and–markdown-outputto specify LaTeX or HTML output. This is especially useful for streamlining automatic documentation generation from gloss texts.

Install the latest version of gliss with gem install gliss (and, optionally, gem install maruku).

One aspect of gliss that some users who don’t have much exposure to git find confusing is how it selects a range of commits to process. Ordinarily, you’ll invoke gliss with two arguments: FROM and TO, both of which can be SHAs, branch names, or tag names. The gliss on-line help tells you that this will process all of the commits reachable from TO but not from FROM. If this doesn’t make a lot of sense, or if you aren’t sure what it means to be “reachable” from a branch or tag, read on.

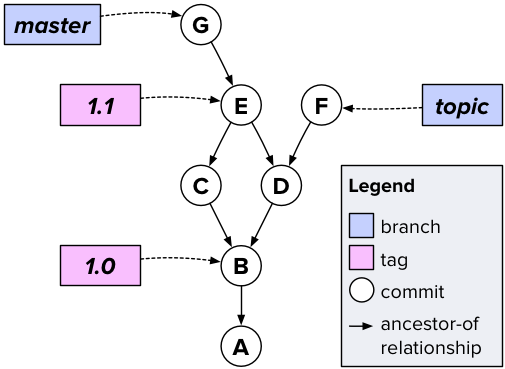

The image above shows a simple git repository. In this image, commits have a single-letter identifier and only contain a pointer to their immediate ancestor. By transitively following the ancestry relationship, we can get from any commit to the root commit of the repository. Note that git commits under the ancestry relation form a graph; more specifically, it is a directed graph (because ancestry is not a symmetric relation) and an acyclic graph (because a node may not transitively have itself as an ancestor).

In this diagram, we have two branches: master and topic, and two tags: 1.1 and 1.0. Tags are essentially immutable pointers to particular commits; branches are pointers that can track a stream of development. A is the root commit, B is the commit pointed to by 1.0, E is the commit pointed to by 1.1, and so on. Let’s look at some example gliss use cases to see how we can use this information.

Say we wanted to see what had changed between tags 1.0 and 1.1. We’d give 1.0 as the FROM argument and 1.1 as the TO argument. This would examine all of the commits reachable from 1.1, but not from 1.0. The commits reachable from 1.1 are A, B, C, D, and E (E is a merge commit, which is why it has multiple parents); of these, B and A are also reachable from 1.0. Therefore, in this case, gliss would only search for glosses in C, D, and E.

Alternatively, we might want to see which commits were reachable from topic but not from master. In this case, gliss would process only F. Note, however, that the TO and FROM arguments are not interchangeable: using gliss on the commits reachable from master but not from topic would give us the glosses C, E, and G.

Please contact me or file a issue report if you have problems with or suggestions for gliss. I hope you find it useful!